In June, I chatted to an old friend, Bob Dryden at the BAA’s summer meeting at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (RAL). I first met Bob when I started in astronomy, watching comet Hale-Bopp cross the night sky before I went to university. To my horror, I realised that this was over 20 years ago!

At the time, we had moved to Abingdon (near Oxford) where Bob was (and still is) an active member of the local astronomy society, Abingdon AS. Bob helped me when I was an enthusiastic but incompetent beginner, when every view through an eyepiece was a new object and every telescope exciting with promise.

During our conversation, he was telling me about his passion for variable stars and how, if I started observing these objects, I would still be able to enjoy visual observing and be doing something useful to science. It piqued an interest as variable stars is something I had been interested in but never really bothered with.

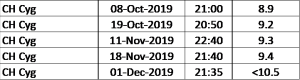

After some online reading, I had a list of objects worth for the autumn skies and began my first measurements using my tripod-mounted 28×100 APM binoculars. Now, after some months of effort, I have made the grand total of 34 measurements of 15 different stars. Unfortunately, my log book records several more but stupidly I did not note the date or time, making them worthless.

Now with some experience under my belt, here are my thoughts are some thoughts on visual variable star observing.

Why Observe Variable Stars

Observing variable stars is great fun! I love observing the planets and the moon as they are forever changing. Well, so are these stars! These objects brighten and fade over the periods of days and months – some predictably and some not. I have lost count of the number of times I have seen, say the Orion Nebula. And while I look forward to every view it hasn’t changed in all the years I have been observing. By contrast, all the stars I observed in this programme have changed.

The results are useful. The BAA maintain records back into the 1800s that show brightness fluctuations over time. These results are analysed by amateur and professional scientists to understand the physics behind stellar evolution, binary stars and exploding novae. Now an (admittedly tiny) handful of records in the database are mine! Fascinating stuff.

Finally there is a challenge to the process. One has to find the star field (in my case after star hopping), identify the correct star in the field of view, make a comparative brightness estimate (while being cognisant of avoiding any human bias) and then deduce the magnitude.

It feels more useful than collecting deep sky observations for sure!

Literature Search

There is extensive reading available online and in books to help get you started with your own observing programme.

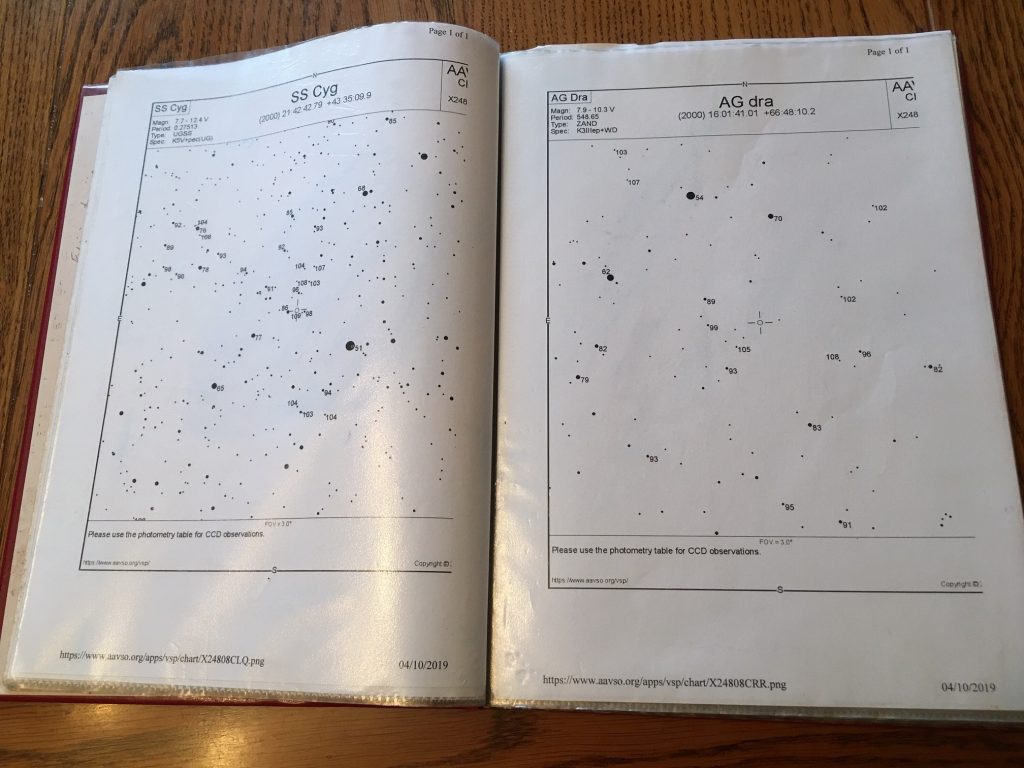

I found the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) particularly useful. Not only do they have articles and features to help you get started, you can print finder charts at varying scales whether naked eye, binocular, telescope or imaging. I use the B charts as they are designed around binoculars https://www.aavso.org/apps/vsp/. They also have many forum posts worth reading.

The BAA has a Variable Star Section (VSS) that publishes a regular Circular http://www.britastro.org/vss/VSSC_archive.htm. Great reading and interesting for the science behind the stars. They (and the AAVSO) frequently publish alerts to gather data for research – including requests from professional scientists.

I found David Levy’s book “Guide to Variable Stars” very useful and a pleasant read. It is well written and makes you want to get outside and start measuring. It includes many descriptions and suitable targets. I bought mine second hand from Amazon for only a few pounds: https://www.amazon.co.uk/David-Levys-Guide-Variable-Second/dp/0521608600

Equipment

I love using my APM binoculars. They are mounted on a heavy-duty Manfrotto 161 Mk2b that has a central column (carrying an altaz mount) that can raise the eyepieces to a comfortably height.

The 2-eyed views are always wonderful and the correct image is very useful for star hopping. With the 19mm panoptics I get 28x power and a 2.4deg field of view. This takes me down to mag 10 (or a bit more on a clear, moonless night). With x2 barlows (giving x56) I get down to mag 11. In fact, 11.6 is the faintest star I have recorded on one particularly clear night while hunting for SS Cygni.

The binoculars have a red dot finder. This greatly aids the star hopping process as I can start from a known bright star before using Sky Safari as a reference. The variable stars are typed in as an observing list and the screen has a circle of 2.4 degrees set so I can star hop in moments to each star in turn where I use the AAVSO printed charts.

The binos also have dew heaters, a dew shield made from an old camping mat and a bino-bandit that shields the eyes from stray light.

Making an Estimate

Estimating the relative brightness of a star requires practice. My method is to study the field of view – once the variable star is located, of course – and compare its brightness to those nearby. It is then a process of bracketing the variable by identifying 1 star that is brighter and 1 star that is fainter. I then judge the relative brightness using 5 steps by estimating if the variable is:

- Equal to the fainter star

- Slightly brighter than the fainter comparison star

- Somewhat brighter than the fainter comparison star

- Halfway in brightness between the 2 comparison stars

- Somewhat fainter than the brighter comparison star

- Slightly fainter than the brighter comparison star

- Equal to the brighter star.

Looking at my notes, I was taking 10-15 minutes or so of careful study comparing the variable star (once I had correctly identified it in the field of view) by judging whether it was brighter or fainter than other nearby stars. With time and familiarity with the star hop and field of view this time came down to several minutes, although I do not hold myself to be an expert by any means!

Minimising Errors

Of course, one has to be careful not to introduce errors into the estimate. Looking at red stars (and a number of Mira and semi-regulars are red) for more than a glance causes them to brighten, a process known as the Purkinje effect. Likewise observing in bright moonlight causes stars to brighten. This can lead to an over-estimation whereby the star is measured to be brighter than it really is.

The advice online is to defocus the eyepiece so that the stars are a disc rather than a point source, thereby spreading the light out into a halo with a lower surface brightness.

In addition to the irregular stars described above, my list includes stars that have periods of many months that should only be observed every few weeks. This is to avoid errors creeping in where the human observer wants to note a change that, due to the long-period of some stars, may not yet be apparent. Luckily the UK weather prevents me from over-estimating as we often get weeks of cloud between occasional clear spells.

My Observing Programme

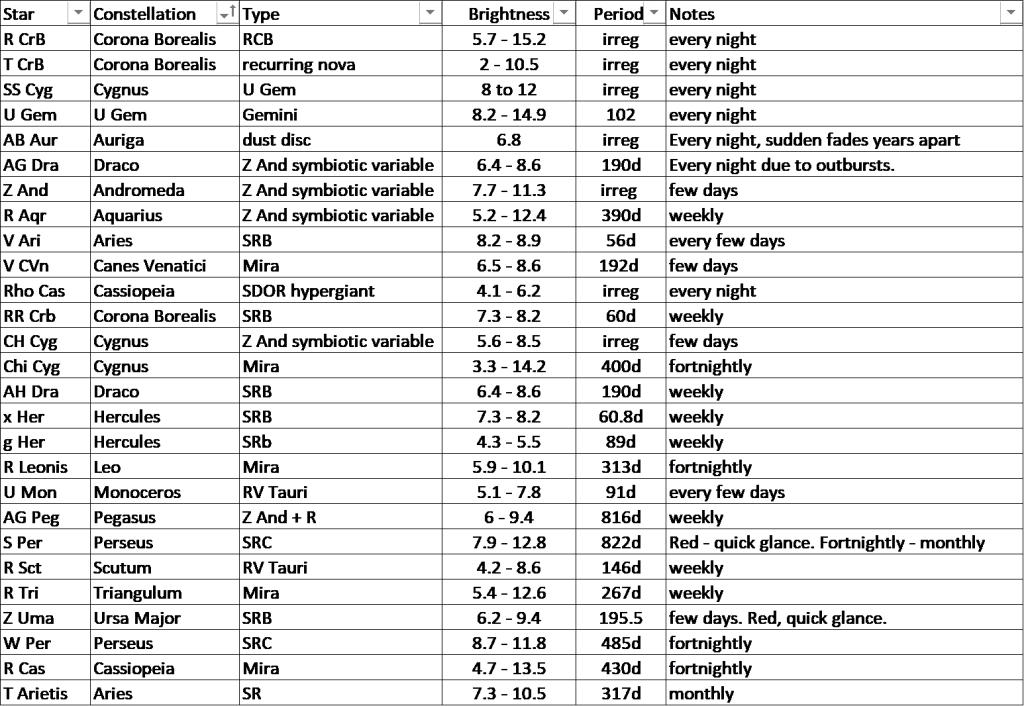

My programme includes stars that are totally unpredictable and are estimated every clear night to see if they have changed. Since June, I have watched R CrB fade from its summer high, brighten for a brief period and then continue its fade. Here are the unpredictable stars I monitor – all within range of binoculars:

- R CrB – a carbon star that fades as “soot” builds on the surface

- T CrB – recurring nova

- SS Cygni – recurring nova (this is only just visible at 11th mag but I look forward to seeing it brighten one day)

- U Gem – recurring nova

- AB Aur – a star hosting a dust disk that may harbour a condensing planet or brown dwarf.

I also have a number of Mira and semi-regular stars on the list gleaned from the references above as shown in the table below. All are within binocular range (or at their brighter phases at least) and visible at varying times from my northern latitude.

The Next Step

I am writing this over my Christmas leave looking out over a damp garden wondering when the skies will next clear. My last observation was made on 11 December and I have not got outside since as grey clouds and cold, wet Atlantic weather systems transit over the UK. Typical, no clear skies when I have time to be outside late at night.

What I do know is that each star will need to be measured as they will all have changed. I can’t wait!